Finding Your Straw Weight for Backpacking

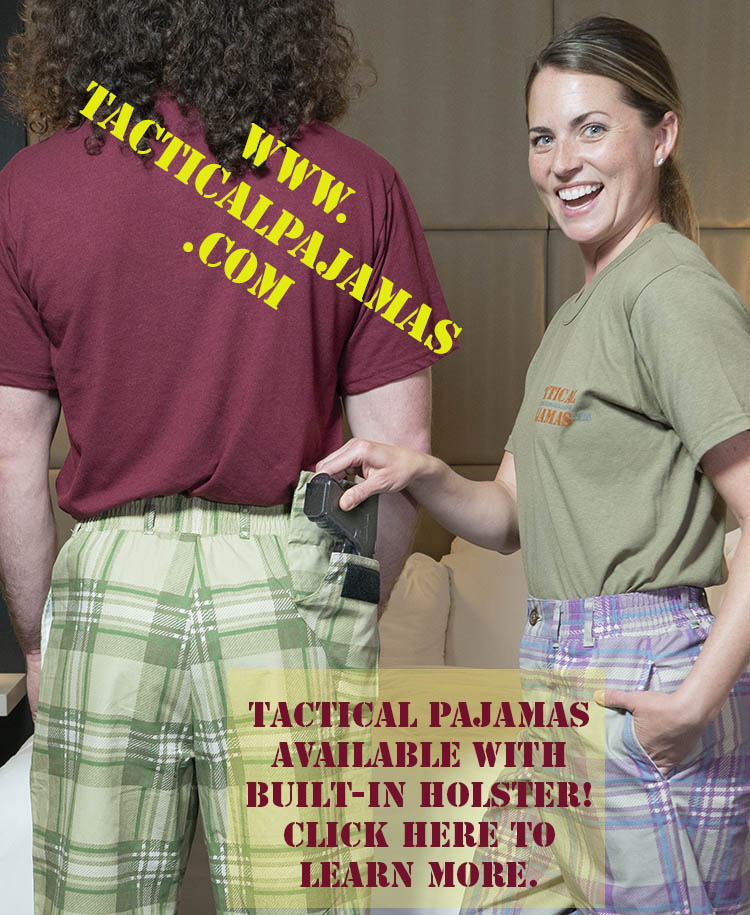

By P.J. Beaumont, co-creator of Tactical Pajamas. Click here for discount codes!

First, let’s get some definitions out of the way:

Base weight— the weight of all your backpacking equipment minus food and water.

Straw weight— a plateau or maximum total pack weight over which your hiking speed diminishes substantially.

You’ve probably heard the story about the straw that broke the camel’s back. If you haven’t, it’s pretty simple. There was a camel that could carry a lot of weight, but if you put the weight of one piece of straw on him beyond that weight, it would break his back.

Though it’s not nearly as extreme, there’s a similar phenomenon with humans. Put up to a certain weight in your backpack, and it might have very little effect. Put one or two pounds more, and it feels like a ton.

On longer backpacking trips, the good news is that your straw weight will go up. There are two reasons for this. The first is because you will probably lose body weight. Start out at 190 and drop to 175, and that’s up to 15 more pounds of food you can carry if you need to. The second reason is because you’ll get in better condition.

The trick is to get these two effects working before you go on your trip.

I use sandbags for workouts a lot, and thus I have many of different weights. I stick them in my backpack and go on long walks. This helps with the conditioning and weight loss, and also one more thing— it tells me where my straw weight is.

Start out low with sandbag weights, five pounds for women and ten pounds for men. Do a mile with the weight, then a mile without. Add a some distance each day and put two more pounds in your backpack every week. For daily training walks I usually only have time to do 5 miles, but I do more on serious weekend training days. You will eventually reach a point where the weight slows you down considerably.

When I’m starting out after a winter layoff, I’m embarrassed to say that my straw weight is about 15 pounds, and that’s after two weeks of hiking five miles a day with no weight (not to mention the other exercise and conditioning I do). I’ll lose a pound or so of body weight per week and build up my leg stamina, and eventually I’ll work up to 30 pounds of pack weight (that’s usually more base weight than I will carry on a backpacking trip). About a third of that is lost body weight and the rest is from conditioning.

During the first few days of winter training, if I’m carrying fifteen pounds I can easily do 18 minutes a mile or better, depending on terrain, and a total distance of ten miles is no problem. Put another ten pounds on and my pace slows to about 23 minutes a mile, and five miles is a slog.

It’s a good idea to use the backpack and footwear you plan to actually hike with. You should take careful note of any problems with rubbing or balance or fit. A backpack that does fine for five miles with 20 pounds might turn into a torture device when carried for ten miles with 30 pounds.

It’s also very important to find out how fast you can hike with a particular amount of weight. For example, if you need to go 60 or more miles between re-supply stops, you’ll have to carefully calculate the amount of food you’ll need to carry. If you go over your straw weight it might take you an extra day to go a certain distance.

Suppose you’re a rank beginner, and your straw weight is 30 pounds. While hikers who’ve gotten their “trail legs” would be able to make 20 miles a day with that weight, in the beginning your mileage might be 15 at best. You’ll need at least 2 pounds of food per day (men) and 1.5 pounds/day for women, plus water. If your base weight (all equipment minus food and water) is 23 pounds, that leaves seven pounds for food and water. Water will be variable, you’ll be picking that up as you walk, but you’ll probably be carrying one pound of it on average. So eight pounds of food. That’s four days worth for men and over five days worth for women.

Your first day will be over your straw weight. How much will that affect you? Hard to say. Suppose you make twelve miles instead of your required 15. 47 miles left to go, and you have three days. You probably won’t make it. Do you need to start out with more food, which will slow you down even more? What happens if you try to tough it out, but you end up having two twelve-mile days in the beginning? With the reduced weight (because you’ve eaten up the food) can you go 18 miles a day on the last two days? Maybe, but maybe not.

Are you hiking through mountainous terrain, or ground that is rocky or muddy? Take off some miles. Bad weather? Take off more.

Experienced backpackers might consider such distances to be short mileage days, but for a beginner they could be accurate. The point is that if you figure your weights and daily mileages wrong you can run out of food, and hiking with no food to fuel you can slow you down even further.

For some people the point at which they reach their straw weight can be gradual, for some it can be more abrupt. Also, you can have several different levels of straw weight, which I refer to as “plateau weights.” For example, someone can have a straw weight at 20 pounds, but between 20 pounds and 27 pounds it’s not that much more stress. Cross the 27-pound threshold, however, and it may as well be 40. It’s a matter of how fast that person can walk a mile in a certain weight range.

Ultralight backpackers will sneer at these weights, as their base weight can be under ten pounds, and some claim as low as seven(!). 18 pounds (including food) can get them through four days of hiking well over 20 miles a day. That super-lightweight equipment can cost a whole lot of money, but the ease of hiking can make up for it in more miles per day and less food a given distance, as ultralight hikers can finish a trail in fewer days.